There is still hope for Shepherd Alley since the alley is currently a blank canvas that awaits the Marriott Corporation to fill in the shapes and colors. A dialog needs to be opened with the community so that there is a synergistic evolution of thinking and use. To quote Jane Jacobs: - "The pseudoscience of city planning and its companion, the art of city design, have not yet broken with the specious comfort of wishes, familiar superstitions, oversimplifications, and symbols, and have not yet embarked upon the adventure of probing the real world." (from the Introduction [pg. 13] of the Death and Life of Great American Cities)

DC alleys and stables were the pulse of the city reflecting the ecology of urban change. Their stories reflect many lives and are living artifacts of 200 years of human experience in Washington. Reconstruction cannot possibly replace preservation. In 1990, all of the properties in Blagden Alley and Naylor Court were recognized by the National Register of Historic Places.

Wednesday, January 19, 2011

Shepherd Alley Update - Razing Hope

A permit is being approved by the Historic Preservation Review Board to bulldoze a one level cinderblock building in Shepherd Ally: - a building that has no historic significance. The applicant is Marriott Corporation, which is an excellent sign for progress and raises hope for potentially humanizing changes in the core of this block. The building to be razed sits on what was once the site of the Woodward and Lathrop warehouse and stable.

Saturday, January 15, 2011

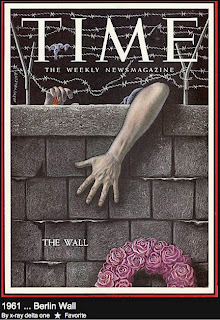

Urban Development Transforms Shepherd Alley into a Stasi Prison-Like Site

Shepherd Alley D.C.

Stasi Prison Germany

The Stasi headquarters (or the ministry of state security of the GDR), from where the dreaded secret police kept, in truly Orwellian style, an eye on “dissidents”, has been turned into an archive and museum. This anonymous block of buildings was ransacked by angry mobs in January 1990, after which the organization shut down.]

100 years ago, at the turn of the last century the planning and development picture for Shepherd Alley was complete. Over the years there were minor changes. Businesses came and went, juts like today. One major change was building a large warehouse and stable for the giant department store Woodward and Lothrop - now long vanished. (see below)

“In Shepherd Alley as many as six different families reportedly lived in the same small house; generally, however, crowding was not that severe.” The average was 1.6 households per dwelling. In this early block map it’s easy to visualize the density of dwellings and imagine the interconnected community. Shepherd Alley (the block embraced by 9th and 10th Streets and L and M Streets) was once the backbone of an integrated late 1880’s block. The alley was ringed by elegant Victorian row homes on the perimeter of the block. The interior had small and large stables, a few small crowded dwellings and an assortment of businesses.

(Page 85 Alley Life in Washington Family, Community, Religion and Folklife in the City 1850 – 1870, James Borchert, University of Illinois Press 1980]

As buildings on the periphery of Shepherd Alley progressively deteriorated, collapsed or were burned by homeless vagrants, large gaps began to appear in the outer shell of the block. These voids became progressively filled by parking lots. In the 70’s a Victorian home on 9th Street was bought for $3,000 because few wanted to live in such a crime-ridden environment. Newspaper editorials proclaimed that the 9th Street NW corridor would never, ever be rebuilt after the riots and conflagration. Parking lots became placeholders for development. It was probably not a bad thing for a community to wait until time and money had caught up to the need and capacity of the neighborhood. Developers quietly and sequentially acquired adjacent properties at bargain prices and eventually towering, massive buildings replaced the Victorian row houses and they then became the new walls of the periphery of the block.

Horses and carriages outside of Woodward and Lothrop In the early 1860’s the city blocks in Washington were loosely populated, however this was soon to change with the post civil war population and building boom. Daniel Nairn wrote elegantly about “The Physical Evolution of Blagden Alley-Naylor Court” in Greater Greater Washington. http://greatergreaterwashington.org/tag/Shaw/ The two blocks that Nairn pictured were immediately north of Shepherd Alley and are reflective of the general progression of alleys and blocks in Washington at the time. The original lots had been laid out in the 1790’s and plats of this block still exist from 1797. It’s easy to see the interplay between commercial, civic and residential buildings in Nairn’s creative 3-D 1888 map of Blagden Alley and Naylor Court. There are about 170 “named alleys” in Washington D.C. Just like people, some alleys became famous, some became historical footnotes and many simply disappeared from the modern urban landscape - victims of the 1934 Alley Dwelling Elimination Act. The alleys had provided cheap housing, small stores, large warehouses and stables following the Civil War years during a great migration of diverse people for many reasons into Washington (50,000 between 1860 and 1870). The alleys became alive and vivacious communities providing cheap housing for an impoverished population that could not find housing elsewhere in the city during these boom years. Conditions were atrocious, crime was rampant and disease was everywhere. Life was difficult for those who eked a survival in the alleys. The city planning process essentially ignored alleys and treated them as hellholes, so deterioration was self fulfilling and inevitable. Yet, the alleys managed to develop a sense of personality and community, frequently reflected in their name (e.g. Blood Alley, Pig Alley, Blues Alley, Tin Pan Alley). Some were simply possessively christened after people of historic significance in the community (e.g. Blagden’s, Cady’s, Nailor’s, Shepherd’s). |

The inner core of the block however, was largely ignored in the planning process of these large peripheral buildings. The street side of buildings was traditionally felt to be more important than the alley side. It’s a matter of published public record that some high visibility senior government planning officials view alleys as being of value for only two things (a) trash and (b) services. Their planning decisions throughout the city have been reflecting this mindset.

The core of Shepherd’s Alley has become a barren wasteland of garbage bins, link fencing, rows of barbed wire and large building underground garage access portals. Young new residents moving into D.C. and living in the new condos repeatedly and loudly complain about criminal activity in the alley and in their underground parking lots accessed through the alley. Street access would have eliminated this problem and created the opportunity for the interior of the block to become a more hospitable place for pedestrians, pets and cyclists.

Berlin Wall

Hundreds of yards of razor wire line high link fences, embellishing the penal appearance of Shepherd Alley. In a classification system of alley salvageability for historic preservation and development, Shepherd Alley qualifies at the very lowest level ranking (1 out of 5). There are almost no remaining intact historic buildings and the opportunity to create a pedestrian “mews” with ties to architectural artifacts of the past has vanished forever.

While the articulated mandate of the D.C. Office of Planning is to increase the density of living in Washington, neglecting the core of blocks results in lost opportunities for not only increasing density even further, but also to create a warmer human experience of living in Washington. Shepherd Alley has taken on an oppressive and depressing Karma. It’s so foreboding that few people ever walk directly through the alley. The large new developments have literally turned their backs on an opportunity to increase density and diversity of living that lies right in their own back yards. Perhaps the community can have a voice to influence the Phase II development plans of the Marriott to include some forward thinking about looking backwards into the alley as a place for pedestrians, neighborly contact and renewed vibrancy. Living today with alley codes, laws, rules and guidelines that were written for a very different world of yesterday are serving us poorly as we try to built into the future.

Glimmer of Hope: A little park on 10th Street has been recently dedicated in this block and this is a heartening step in the right direction. Sadly, the push for this oasis came through the community with project champions like Jim Loucks ( http://www.10thstreetparkfriends.org/?page_id=2 )rather than originating spontaneously from higher levels of government planning. Various levels of DC government gradually and steadily bought into the project, and took ownership. It is now almost finished. Even though the park is part of the peripheral wall of the block and not directly a part of the alley, it nonetheless will have a remarkably humanizing effect on Shepherd Alley by drawing people into outdoor spaces. There is now a warm buzz of enthusiasm and hope for more of this sort of thinking that is percolating through the community.

To consider only the outer shell of a block in urban planning and to ignore its equally important interior elements seems wasteful and regressive. The inner and the outer elements are architecturally interconnected and functionally interdependent. There can be a graceful ecological synergy between the elements. The alley revival movement is catching fire in many cities, as the realization dawns on inhabitants and planners that overzealous development has resulted in the creation of dehumanizing, depressing and monotonous monoliths. Increased density living potential is being achieved, but the real question should be whether an environment is being created that is attractive for people to move into Washington and stay. Alleys can become the pulse of a city if properly managed. They can also lead to the death of a community if improperly managed. People will either leave the community if they are already here or they will refuse to come if they have been thinking about relocating to inner DC.

An afternoon walk through the Cady’s Alley and Blues Alley in Georgetown should reassure even hardened alley abolitionists of the great potential that alleys hold for synergistic development. The responsibility for the intelligent planning and nurturing of alleys should be a high priority in any city’s Office of Planning and Historic Preservation Office. I’m sure that Jane Jacobs would have agreed!

With such attention paid to detail and beautiful execution lavished on the outer perimeter of Shepherd Alley, (just as at the turn of the last century) it seems a sin of urban planning to create ugly an oppressive inner block through passive disregard.

Turning alleys into neighborhood spaces

Large American cities increasingly are trying to improve the aesthetics, environmental performance, or sociability of their alleys.

“In 2007 the City of Chicago issued “The Chicago Green Alley Handbook,” which is aimed at installing permeable paving, introducing planting, and relieving flooding along many of the city’s approximately 1,900 miles of public alleys.

Recently Los Angeles has been looking at how to create park-like settings or friendly neighborhood spaces in some of that city’s 12,309 blocks of alleys, with encouragement from the University of Southern California’s Center for Sustainable Cities.

Probably the most energetic alley improvement program now under way is in Baltimore, where an organization called Community Greens is collaborating with neighborhood groups and City Hall to reclaim rundown and often crime-ridden rear passages.

Community Greens — an initiative of Ashoka, a nonprofit international “social entrepreneur” organization based in Arlington, Virginia — began working with the Patterson Park Community Development Corp. in 2003 to convert a decrepit Baltimore alley into a place where residents would feel secure and might mingle with their neighbors.

That alley, between Luzerne Avenue and Glover Street in the Patterson Park neighborhood, was outfitted with planters, potted plants, benches, and a barbecue grill. Gates were installed near the ends of the alley, and garbage collection was moved elsewhere — first to areas in front of the houses and later to the ends of the alley.

“It’s been nothing short of transformational,” says Kate Herrod, director of Community Greens. “Where there used to be pimping, crime, and drug activities, they got safety and community.” Residents “feel much more safe and committed to their block” than before, she says.

The success led Baltimore Mayor Sheila Dixon to sign an ordinance in May 2007 that authorizes “gating and greening” of any alley where the adjacent residents overwhelmingly request it and where there is no objection from the city departments of police, fire, sanitation, transportation, and public works. If 80 percent of the owners of the surrounding occupied houses approve it, various improvements can be made to the alley. The surrounding homeowners must consent unanimously before gates, trees, or other obstructions to vehicles can be included in the upgrading.

Patterson Park now has a reported 14 blocks carrying out alley improvements, considering them, or requesting authorization. In all, about 60 blocks in 22 Baltimore neighborhoods have expressed interest in the program.

From the perspective of New Urbanism, the conversion of alleys to communal spaces has both an upside and a downside. Over the past 20 years, new urbanists made alleys an accepted part of contemporary planning, even in suburbs that historically lacked them. Many developments — in cities, suburbs, and small towns — have introduced or reintroduced alleys as a way of upgrading the neighborhood atmosphere. Rear passages have become inconspicuous locations for garages, garbage collection, and some utilities. Baltimore’s move toward closing some of its long-established alleys goes against that trend.

If many alleys are placed off-limits to parking, that could divert parked cars to the streets. One danger in the emerging trend toward converting alleys into private or gated neighborhood spaces is that it could end up reinforcing the conventional practice of putting driveways or garages in front of houses. That very pattern undermined the attractiveness of many American residential streets during the past six decades. However, in Baltimore’s program, off-street parking is sometimes installed at the ends of the alleys.

The specifics vary widely. In a redeveloped portion of Patterson Park known as Dexter Walk, the area behind the houses has been designed to be fairly open to the alley and the neighbors. Residents can drive in and park their cars behind the homes. When the cars are removed, however, the unobstructed expanse of space becomes a good spot for block parties and other neighborly activities. The houses were built without fences between properties, so that the alley and the rest of the rear area could be used at times for community events.

Baltimore’s experiment with new treatments for alleys stems largely from the city’s severe crime problems. The greening and gating of alleys can be “a way for people to create defensible space,” Herrod says. Many alleys have become no-man’s-lands, she observes. “This initiative is really to help residents take ownership over spaces where there are issues of crime, dumping, and vandalism,” Nathanson confirms.” Issue Date: Thu, 2009-01-01

Page Number: 13 (New Urban Network)

http://www.shorpy.com/node/2362 Ambridge Alley PA: 1938

Editor’s Note: Alleys were not always places of unhappiness, crime, disease and despair. Borchert wrote [1] “Alley children displayed few signs of disorder and delinquency – on the contrary, they appear to be well integrated into the alley community. … Through music and other forms of entertainment alley children created their own amusements; and more important, by working through traditional forms they maintained key integrating experiences.”

Monday, January 10, 2011

Strolling through a New York Mews with Teri Tynes

Teri Tynes has posted a delightful vignette about walking through MacDougal Alley and Washington Mews in New York City following the recent snowfall. These preserved horse stable alleys straddle 5th Avenue in New York and illustrate why alleys need not be considered as simply places for trash and services. Many years ago someone in one of the city development offices or more likely, within the community, was thinking ahead when this little enclave was spared the wrecking ball. Alleys like these, humanize the harsh reality that surrounds them. One's heart is warmed strolling through these inner city oases as you think about living in the alley 100 years ago when the horses and their owners struggled with blizzards like this.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)